Growth versus value

“Maybe some of the old traditional value names are actually, much less risky than they were previously”

Edward Heath-Thompson

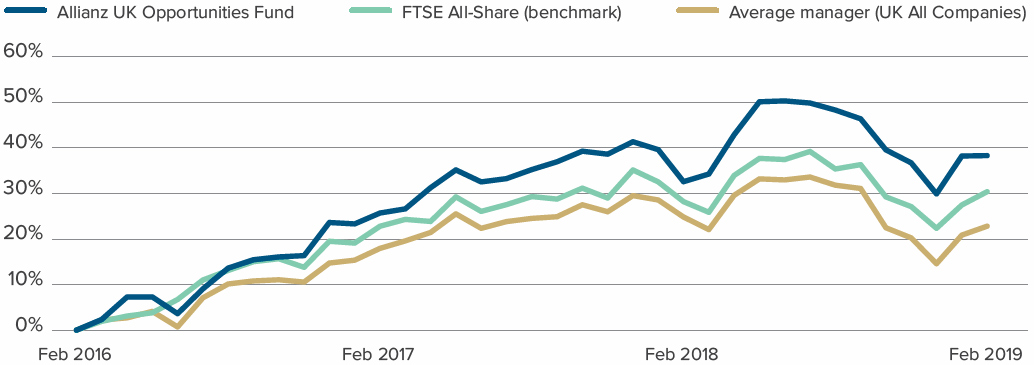

Matthew Tillett describes his Allianz UK Opportunities fund as an unconstrained, concentrated ‘go-anywhere’ UK equity strategy that employs a ‘simple’ investment philosophy.

The fund typically holds a portfolio of between 30 to 50 stocks, typically above a £50 million market capitalisation. Tillett assesses valuations and downside risk before investing in a stock.

While he is very much a ‘value-orientated’ investor, he does not simply buy things because they are cheap. He sees this as a common mistake a value investor can make. ‘It’s the downside risk that matters more than the upside. If you get the fundamental analysis right and the business performs as you think it’s going to, the upside takes care of itself because you’re buying things cheaply enough,’ Tillett explains. ‘Where you go wrong is when you get the risk analysis wrong, and risk is a key part of what I’m doing. By risk, I mean the intrinsic risk to the business and the stock. I’m not really talking about volatility. I mean business risk, financial risk, valuation risk and the risk of overpaying.’

As a consequence, even though the Allianz UK Opportunities fund is very much a value fund, it does not currently have significant exposure to some of the household sectors one commonly associates with this approach, such as banks, telecoms and energy. ‘We did have quite a lot of exposure to those sectors but less so now as I’m now struggling to make investment cases for them work,’ Tillett says.

The volatility in the final quarter of 2018 set off the age-old growth versus value argument once again, as investors debated whether the turbulence was the trigger to rotate out of growth stocks following the long bull run.

IRONING OUT STYLE RISK

However, Peters does not believe investors should be restricted by growth or value styles. He points out that for around four years up to 2007, most fund managers he met had a value bias, the majority of whom had performed really well. ‘I remember thinking: “why the hell would anybody want to be a growth investor?” Roll it forward to 2019, why would anybody want to be a value investor?

‘We’ve had the big names in the sector all having some variation of their growth approach, and everything sounds rosy in the garden. But things are cyclical, things will change, things will die. So I don’t think it’s right to rule out any particular way of running money at this time.’

This view resonates with Ripton, who highlights there are massive periods when either growth or value have outperformed. Over the past three years, he has focused heavily on managing out this style of risk by combining funds within portfolios. ‘We’ve probably had more value than we would have wanted over that period of time. But essentially we still continue to think having a more balanced approach really does work,’ he says. ‘Everyone looks at value versus growth, but we think that’s not necessarily the right way of looking at it.’

Zafar is another who believes playing value off growth is not necessarily the right approach. ‘It’s the excess return of value or the excess return of growth that you’re interested in at any point in time. And when you look at that versus what stage of the cycle you’re in, what you find is value has a very specific market environment when it really does fantastically well,’ he points out.

‘But the fantastic performance is quite optical as at the same time growth does horrifically. That part of the cycle is recessions. So, when you get to a recessionary environment, you don’t want to be going anywhere near the growth style, and you want to be holding as much value as you can.’

In essence, Zafar’s point is that when you get a recessionary environment you do not want to be going anywhere near growth, and hold as much value as you can. Based on the current uncertainty in the economy, he has tilted towards value having been significantly overweight growth for a period of time.

‘When it comes to the UK, though, especially versus other international markets, you tend to have more value-orientated sectors and, consequently, more value-orientated fund managers,’ he points out. However, he is reluctant to ‘bet the farm’ on value, with central banks seemingly happy to continue supporting markets, especially when it comes to the UK.

Lagarias is not so fond of value, though, with the widely differing definitions of the style an issue for him. ‘With growth, I know what I’m buying. I know I’m buying a specific product or a suite of products and a specific vision that has been producing acts so far,’ he says. ‘With value, there are as many definitions as there are fund managers. The problem with value is you need to get other people to see it as well. You need to be the first one to jump in, and then you need the rest of the wave to come to your way of thinking.’

CLEAN UP

Toolan does not share Lagarias’ view, especially in the current environment where potential future earnings are being heavily discounted. ‘The reason growth has outperformed for so long is the discount rate has been so low,’ he says.

‘For so long the market is discounting back those cashflows further and further into perpetuity and that’s actually quite dangerous. Whereas, with value you’re actually looking at much shorter-term cashflows so there’s less that can actually go wrong.’

While employing a value approach, Tillett is reluctant to describe himself purely as a ‘value’ investor because it means different things to different people. Ultimately he looks at absolute value in a bid to generate positive returns.

He says: ‘[I’m] not blind to growth as well. If you look at my portfolio, I think it’s growing earnings at 12% a year. That’s almost double the UK market. I think it’s got a return on capital of 15%.

‘It’s got lower leverage than the market and a price/earnings ratio of 10 versus 12 on the market, but I get that by doing it in an all-cap way and not necessarily buying all of the classic value stocks in the FTSE. Some of them may look cheap, but they’re not that interesting.

‘UK equities haven’t always been like that, but I think right now they are like that because there has been a constant barrage of negativity for the last three years.’

An interesting feature in this current cycle is that quality growth has outperformed throughout, a trend that has rarely happened in the past. The concern for some is how this segment fares in a downturn.

Among those worried is Heath-Thompson, who has been adjusting his positioning to compensate for this concern. ‘Counterintuitively to where we are in the cycle, we have been increasing our value exposure because of that, because we’re seeing a lot more opportunities in the value part of the market,’ he highlights.

‘If you take some of the bank stocks, RBS for example has obviously cleaned its business up and reduced a lot of risks. So actually it could be a defensive stock. So maybe, some of the old traditional value names are actually, much less risky than they were previously.’

BEING ACTIVE

The Financial Conduct Authority’s recent crackdown on the asset management industry has forced active fund firms to be more transparent about their fees. One of the areas the regulator inspected closely was the Active Share, which represent the percentage of stock holdings in a fund manager’s portfolio that differs from the benchmark.

The ongoing charge figure in the Allianz UK Opportunities fund is capped at 54 basis points and it also runs a performance fee-only share class. Citywire A-rated Tillett believes fees for the style of fund he runs have gone down as far as they can go given the all-cap nature of the fund.

‘This type of fund is always going to have quite a lot of mid and small caps,’ he says. ‘It’s never going to be scalable into the billions, so I don’t really see how the fees can come down any further without it not being economic for these kinds of funds.’

Ripton stresses there is a difference between having a high active share and just making sure you do not have a pure mid and small-cap bias. Essentially, he says this means a portfolio should not follow a benchmark, but at the same time be representative of some of the risks that are being taken.

‘A lot of the time what we’ll do is buy active managers and we’ll actually hedge out the underlying market on the other side of that. So, what I am really playing is that alpha generation. But what I want is something that is going to be vaguely representative.’

CONVICTION

Toolan wants his UK equity funds to have a high active share, so he tends to be drawn to those managers who run more concentrated portfolios, as they are less likely to hug the benchmark.

‘I wouldn’t necessarily say running a long list of stocks is a bad thing. It’s not a concept I’ve personally ever been that comfortable with,’ he says. ‘We would typically look at more concentrated portfolios, as we want something that’s got a high-conviction portfolio.’

The sectoral composition of the UK is one of the unique features of the market. This diversity means, when you get down to the mid and small-caps end of the market, you can find plenty of consumer discretionary plays, which are more of a rarity among the large caps. On this basis, Zafar prefers not to look for active share as you can be ‘beholden’ to the benchmark you’re comparing the fund manager to.

‘Whether it’s a concentrated portfolio of stocks, or a 200-stock portfolio, it really comes down to the kind of processes being run. If you’ve got a team of analysts where you can cover 200 stocks, that’s perfectly fine,’ Zafar says.

‘From our perspective, our clients want us to show some sort of conviction in the managers we hold on the buy list.

‘We prefer the managers we have on our buy list to reflect that sort of conviction in their portfolios as well, where their process is appropriate to do so.’

For Wyllie it is a little too simplistic and potentially dangerous to say a high active share is always good and low is bad. He feels the debate is really on whether a 1%-to-2% return above the benchmark at low tracking error can be achieved on a consistent basis and at an appropriate fee level.

He says: ‘It boils down to whether you’re looking at your portfolio construction through the lens of an asset allocator or a multi-fund solution. If you’re an asset allocator, you’re more likely to say: “actually, these are the indices I’ve modelled, and I’ve got to be careful how far I deviate away from those ”.

‘You might have a core and satellite approach, but you’re always going to be cognisant of the basis risk between your modelling and what you’re actually holding. But if you’re a multi-manager, you see yourself as being paid to go out and find alpha. So you’re probably going to lean much more in favour of more concentrated portfolios.’